As is so often the case, historical context helps us understand our ancestors’ lives and choices. Surprisingly enough, our story begins with Napoleon. As the History Channel so capably summarizes (here), Napoleon was a French military officer during the time of the French Revolution (1789–1799) who rose through the ranks far beyond his peers until he was appointed commander of the entire military in 1796. Three years later he engineered a coup that set him at the top of the French Republic. Eventually, in 1804, the Senate declared him Emperor of the French.

Even when he was fighting on behalf of the revolution, Napoleon sought to conquer territory far beyond what many would consider traditional French territory. Nothing changed in that regard when Napoleon became emperor. If anything, his quest to expand French control only increased.

Of course, the other powers and nations of the day did not wish to serve a French emperor, so both individually and, more often, in alliance they battled Napoleon wherever his armies sought to go. The coalition that interests us most is the fourth, which included Britain, Prussia, Russia, Saxony, and Sweden and spanned the years 1806–1807.

What is of most interest to Mennonites and us Bullers happened during these years. In August 1806 the Prussian king Frederick William III, for reasons not entirely understood, went to war against Napoleon all on his own, with no help from his coalition partners or his military ally Russia. The results were devastating. In the space of nineteen days the Prussian army of 250,000 was literally decimated through the deaths of 10 percent of its soldiers; another 150,000 were taken as prisoners, as well as 4,000 artillery pieces and over 100,000 muskets (see here).

Not only was the Prussian army destroyed completely as an effective fighting force, but Napoleon also added Prussian territory to his realm. The effect of all this on the psyche of the Prussian/German people was devastating, and it prompted the Prussians, after Napoleon’s advance was turned back and his power weakened by the Russians in 1812, to rebuild their offensive might as fully as possible and to add to that a second layer of military capability available for protecting Prussian home territory.

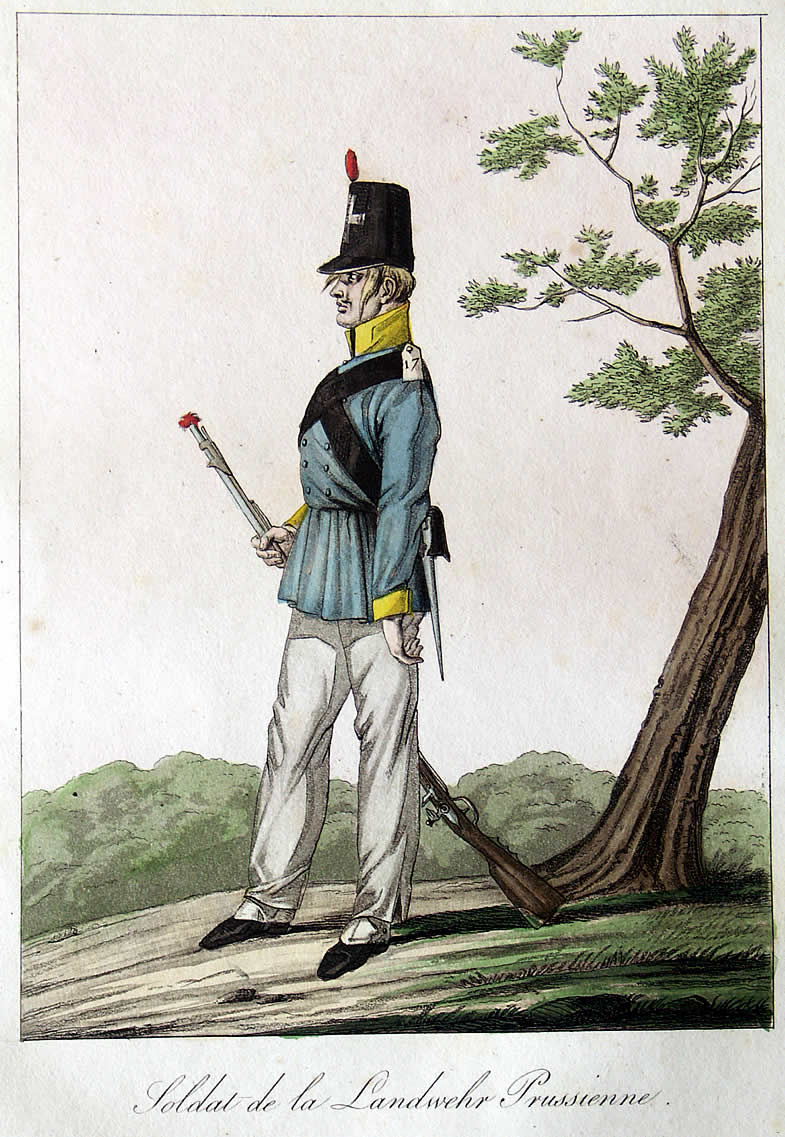

|

| Soldier of the Prussian Landwehr |

As might be expected, the edict was enforced with different degrees of rigor in different regions and likewise encountered different Mennonite responses from place to place. Some government officials overlooked Mennonites who did not comply, while others sought to register every last male. Some Mennonites refused to be registered at all (even though registration did not automatically lead to military service), while others adhered to the law. Of interest to us is Adalbert Goertz’s record of registrations for the Schwetz district, which reveals that all males regardless of their age were registered, including Jacob Buller, 56; Heinrich Buller, 26; Jacob Buller, 9 (all from Przechowka); and Jacob Buller, 45 (Ostrowo Kämpe; see here, table 8).

Although it seems that only a few Mennonites actually saw action, and that generally voluntarily, the proverbial writing was on the wall. The long-standing exclusion of Mennonites from military service was slowly but surely eroding.

It is probably no coincidence that Mennonites—and Bullers—in the Neumark and the Schwetz areas began to immigrate east to Volhynia and Russia during the following several decades. Indeed, all but a handful of members of the Przechowka church moved to the Molotschna colony in 1819–1820 and 1823–1824. As we noted previously (here and here), all the Buller families likewise disappeared from the Neumark area between 1806 and 1826. The most reasonable explanation is found in the growing movement toward universal conscription (i.e., all males subject to the draft) within Prussia during this time. (There is no better account of this development than that found in Jantzen 2010.)

The Mennonites who left in the 1810s and 1820s were shown to have acted wisely in the early 1830s, which is when we take up the story with regard to Neumark (this is not to say that other Mennonite areas were unaffected; they were, but our concern is Neumark). On 16 May 1830, the Mennonite Edict of 1789, which previously had been operative only for the province of Prussia (not the entire Prussian kingdom), was extended to West Prussia (i.e., including Neumark and the Schwetz area) as well. Stated simply, this edict gave Mennonites a choice: serve in the military, like all other Prussians, or pay an extra tax and suffer the loss of some civil rights, including the right to buy land that was nonexempt (i.e., that carried the responsibility of military service).

The extension of the edict’s terms over the Neumark area met with stiff opposition, as “all forty-three heads of household [in Brenkenhoffswalde] went on record as rejecting the option of serving in the military” (Jantzen 2010, 115). When officials attempted to collect the additional taxes and to limit the sale of property according to the terms of the edict, the Mennonites appealed to Frederick William III to uphold the terms of their charter. Frederick “said that he would like to help the Mennonites, but he could not exempt them from the obligations borne by other citizens” (Klassen 2009, 87)

Over the course of the next few years, therefore, the Neumark Mennonite communities arranged to leave their home of seventy years behind. Elder Wilhelm Lange (here) negotiated permission with the Russian government for forty Mennonite families to emigrate to the Molotschna colony, and so it was that

in the summer of 1834 twenty-eight Mennonite families and ten Lutheran families who had joined them left for Russia. There they established the community and congregation of Gnadenfeld. Just as this group had transmitted important impulses from the Awakening movement to the Vistula Mennonites, now too their congregation became a transmission belt for infusing Mennonites in Russia with new attitudes toward missions, education, and spiritual renewal. (Jantzen 2010, 117)

As noted earlier (here), these “new attitudes” played a key role in the development of the Mennonite Brethren movement during the middle of the nineteenth century.

Although the spirit and values and descendants of the Neumark Mennonites lived on in Molotschna and far beyond, the community ceased to exist in 1834. There are no doubt Bullers buried in and around the villages of Neu Dessau, Franztal, and Brenkenhoffswalde. Their headstones are no doubt gone and their graves forgotten, but we have resurrected some of their names from obscurity, and we will continue to do the same for other Bullers who are part of our larger family.

Works Cited

Jantzen, Mark. 2010. Mennonite German Soldiers: Nation, Religion, and Family in the Prussian East, 1772–1880. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press.

No comments:

Post a Comment