At the end of the previous post Heinrich Buller found himself without either parent and in search of a trade that would sustain him. We pick up the story there.

[10] About this time, a distant relative of his—a-kind-hearted woman—offered to lend him fifteen Rubles to pay his way to Russia. He hesitated to take the offer but finally did so and came to a village of Mennonites called Gnadenfeld (in the Colony beside the Molotschnia River). Here again he picked up a new trade, and this time it was blacksmithing because this business offered the best wages. Father had, as we can see from the above, passed through a period of great unrest and changeableness. He had in fact changed trades so often in the course of a few years that people were beginning to lose faith in him. They frankly told him that they did not like his vacillations and lack of stability. This work from the mischievous Dame called “Rumor” made it quite hard for him to get a job and to keep it. Nevertheless, he was lucky enough at last to find employment with the blacksmith and for several years he worked steadily at the trade and, as times were then, made good headway.

A cousin of father’s by the good name of Peter was also a blacksmith and lived at the village of Alexanderwohl. He had gained quite a bit of local notoriety as a mechanic of outstanding merit, and the whole village was sounding his praise. Having had repeated invitations from this distinguished relative to come over and pay him a visit, father at last decided to do so. No sooner had he arrived here than his ears were filled with the praise of his worthy kinsman, seasoned, of course, with many a fulsome joke at his expense. The universal opinion of the little village was, of course, that Peter the Great was incomparable and had father so badly outdistanced (bested) as a blacksmith that he stood in a class by himself. Father may have felt a good bit of chagrin over this incident, but in any case (despite a fiery disposition) controlled his temper well. The fullness with which he related the incident leads me to believe that he must have smarted a good deal under this scoffing. However, to be short, father visited the shop, found his cousin busily at work and his boss looking on with evident satisfaction. A casual scrutiny of some of the work that aforesaid Peter had finished satisfied father that he could [11] teach him a good many things as an artisan at the anvil and forge. For courtesy’s sake, however, he refrained from any disparaging remarks; in fact, he had only words of approbation, disingenuous though they were. All would no doubt have passed off in this quiet manner had not Peter’s boss in a voice of exultation called on him to offer some criticism if he dared. This public challenge was more than father could stand, and he proceeded to lay bare all the weak points of his cousin’s workmanship. It so chanced that a wagon stood finished in the shop. Bit by bit he went over that job, pointing out here and there all the mistakes of construction—the flimsy work and crudeness of it all. “If that is the meaning of your words,” said father to Peter’s boss, “that I’m to play the part of critic here, then my is attitude altogether a different one from that of a friendly visitor,” and with that remark he went over the whole wagon with the eye of a critic, calling attention first to the wheel, the tire of which the unlucky Peter had made somewhat too loose over the felloes so that at full many a place the daylight peeped through between tire and felloe. “But,” he said, “this is not the only slipshod piece of workmanship. Look for a minute at the tire itself…,” and with that he called attention to the weld of the tire. Here cousin Peter had drawn out the iron to half the normal thickness of the tire, making it not only the weakest spot but also most rude and amateurish in appearance. He then proceeded to tell them how he made tires and how he made them fit tight and solid upon the felloes—methods which even to this day are practiced by village blacksmiths all over, showing that they were based on sound principles.

It would be quite impossible to enumerate all the details to which he called attention. Suffice it to say that under his direction, many a feature stood out plainly, which offended common sense, and were quite ridiculous in shoddy workmanship. It was evident that the master workman of this shop had little or no sense of proportion or of symmetry. Thus, for instance, he had made a kingbolt so light and thin that the first unusual strain would be sure to break it. Then, too, he had equipped it with so small a head that it was only a matter of time before it would wear its way through the wood and cause extreme annoyance to the luckless owner. Then, too, at all points where rivets were used, they said Peter had evidently paid little attention to either looks or utility. For instance, he had used rivets with small heads indiscriminately by the side of those [12] with large heads; or again, he offended in another direction by using rivets that were obviously too long, consequently he had to bend them into the woodwork when he hammered the ends. Evidences of this flagrant abuse were easily found all over, and it goes without saying that father exposed all of them to the onlookers.

I have given this little story with considerable detail, not only because it shows how he could vindicate himself when called upon to do so, but also because it well illustrates what a careful workman he himself was. He was slower on this account than other workmen, but his work was done with a thoroughness and neatness that displayed an artistic temperament. His work he always guaranteed. His methods were, of course, not the kind that was calculated to enrich his pockets but rather to give satisfaction to customers. He believed in doing a thing well above everything else. So in his field, he was an artist to whom a crude job always gained pain.

For several years more father plied his trade, but then followed a series of poor crops, which necessarily affected his business much. It began to be increasingly hard for him to make a living at it. So finally he hired out to a man for 100 Rubles per year to do jobwork for him. This new-found boss was a surly, fault-finding man and often abused father. Now father always had as one of his assets a considerable store of temper. So it happened that he could not forever stand this abuse but finally resented it with the inevitable result that he lost his job. On the same day, however, another man came and hired him. His job was to make buggy springs. The material to be used was so poor that, try as he would, he had no success in making them, and, of course, once more he lost his job.

After this he worked by month or day just as it chanced and at any job that offered itself. Again the country suffered from poor crops, and so in the fall of the year he went with a friend by the name of Daniel Penner (a compatriot from Poland) to Fidosia in the Crimea of Russia), or to be exact, to a place about 25 Werst (15–18 miles) from this town (village of Friedenstein, Crimea), where he again hired out as a blacksmith and labored several years. Here, too, he met the young woman whom he afterwards married—Aganetha Duerksen. He had met her four or five years previously at the home of her [13] brother Benjamin Duerksen. That, however, was entirely a chance meeting, as the following incident will show.

It is a custom practiced through Europe that the labor year dates from about the middle of November each year. All employers of laborers, who hire out for year, hire their men at that time, after which the laborers have one week in which they can do as they please—sort of a “labor week” akin to our “labor-day”—which often was spent in visiting or relaxation. After this period of relaxation, they once more have to begin to work for their masters. This week is called “Mateen.” It was this time of year, about 1861, that father had been at work for a man at Alexanderthal but had just hired out for two years to a certain Kroeker who owned a blacksmith shop at Landskron. Before beginning to work for this man, he decided to visit his old friend Karl Penner who lived at Gnadenfeld. He spent several days there and then on a nice Sunday set out on foot to walk over to Landskron to put in his appearance. Accordingly, having all his extra clothing tied in a bandana handkerchief, he was on his way when all at once he noticed a carriage driving up. They met, and to his surprise he found that they were old acquaintances. They were three women: Mrs. Dan Unruh (?), her daughter, and another woman. Friendly greetings were exchanged, and they insisted he should accompany them to the village of Waldheim. He protested, explaining that he was not acquainted there, but to no avail. So he drove along with them, and when they arrived at Waldheim, they drove up to the house of Benjamin Duerksen. As already noted above, Aganetha was staying there at the time, and so an acquaintance was made that several years later ended in matrimony.

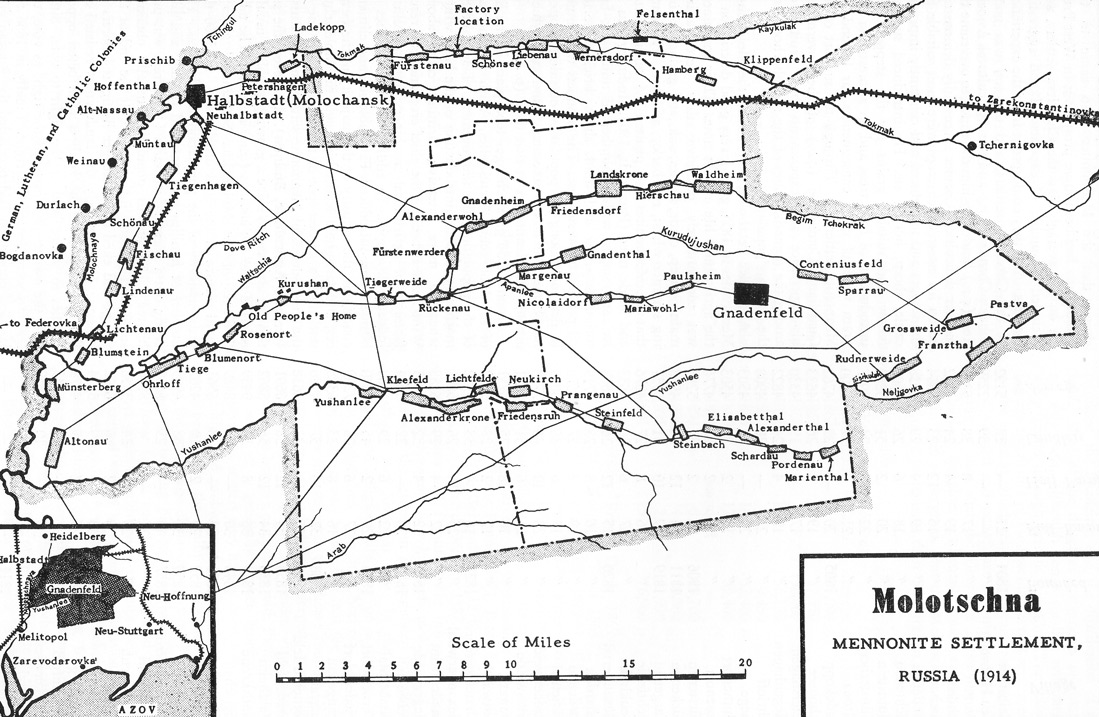

1. We have encountered Gnadenfeld before, as the Molotschna village founded in 1835 by a group of Mennonites primarily from Neumark but also from Deutsch Wymsyle (see, e.g., here and here). Being from Deutsch Wymsyle, Heinrich went there first when arriving in Molotschna. Gnadenfeld (see further here) was located roughly 11 miles east–southeast of Alexanderwohl and about 4 miles south of Waldheim.

2. The reference to a cousin by the name of Peter in the village of Alexanderwohl is intriguing. Of course, the cousin—assuming a first cousin is meant—could have been from Heinrich’s mother’s side (perhaps a Goertz) or his father’s side (thus a Buller). We know of no Peter Goertz in Alexanderwohl, but there were at least two Peter Bullers in the village at that time. Presumably one of them is meant.

3. Blacksmiths in that day no doubt worked on a variety of metal objects, but this story focuses on wheel construction. In evaluating Peter’s Buller’s workmanship, Heinrich’s account mentions two parts of a wheel that might not be familiar. We can all, I suspect, identify the hub in the center and the spokes radiating out from the hub. The wooden piece to which the outside ends of the spokes attach was the felloe (or fellow or felly). The tire, which we generally think of as rubber today, was the other metal ring that not only held the whole together but also made contact with the ground; metal is obviously more durable than wood, which is why it was used on wheels.

Because Peter’s blacksmithing talent was in his metalwork, Heinrich’s evaluation focused on two problems with the metal tire: the tire was not tight around the felloes, and one could see daylight between the two; the tire was not uniform in thickness, being half the usual thickness in places, which would lead it to wear thin much more quickly than it should.

By kingbolt Heinrich presumably means the bolt that holds the chassis (or center beam) of a wagon carriage to the front axle and enables the wagon’s front wheels to be turned. One certainly would not want a bolt too slender to bear the strain it would constantly face.

Heinrich’s criticism or Peter’s work went beyond structural issues and encompassed aesthetics as well. According to the account, Peter used large and small rivets indiscriminately, with no concern about how the finished product appeared.

4. The port town of Feodosia (Fidosia above) is located on the southeast cost of Crimea; the village to which Heinrich and Daniel Penner went, Friedenstein, was located 15–18 miles to the west. I find mention of Mennonites from this village in various sources, but further information about the village (e.g., its precise location) is unavailable. The map below shows the relation between Molotschna (top arrow) and Feodosia in Crimea (bottom arrow).

5. The final paragraph goes back in time a few years and is dated to circa 1861. If correct, Heinrich would have been around twenty-seven years old. The villages Alexanderthal and Landskrone were both in Molotschna: the former in the extreme southeast of the colony and the latter in the center of the colony on the road that linked Alexanderwohl and Waldheim. As the story goes, Heinrich had been working in Alexanderthal but was taken a new job with someone in Landskrone. The path from Alexanderthal to Landskrone led through Gnadenfeld, so he stopped there for a visit, then set out on foot to Landskrone to start his new job. On the way, he was kindly given a ride in a carriage to the village of Waldheim, where he first met his future wife: Aganetha Duerksen.

So ends the Heinrich portion of the story, so the following post will turn to Aganetha’s story as told by Heinrich.

Work Cited

Buller, William B. 1915. Life Story of Heinrich Buller and His Wife Agnetha Duerksen Buller. Parker, SD: privately printed.

No comments:

Post a Comment