The previous post required more than a little concentration, as we tried to keep straight three different Peter Bullers and at least two Heinrichs. This post is a lot lower key—but still meaningful. We return to several questions asked earlier: When did the Bullers leave Neumark? Where did they go?

The answer to the second question is by now obvious, at least for the Bullers of Brenkenshoffswalde: many went to the Deutsch-Wymysle area. The answer to the first question is likewise becoming a bit clearer, again at least for the Brenkenshoffswalde clan. The evidence is right before our eyes.

As we noted in an earlier post (here), all the Bullers and Unruhs were gone from Brenkenhoffswalde by the 1826 land register. From that datum we know that the Bullers who lived in Brenkenhoffswalde in 1806 were gone twenty years later.

From the Deutsch-Wymysle records above, we can narrow the time frame considerably. If you recall, this is the register of Mennonites who came to Deutsch-Wymysle from the Neumark and Schwetz areas. All these Bullers were born somewhere other than Deutsch-Wymysle, which allows us to look at their dates of birth and the latest date a Buller was born in Brenkenhoffswalde (i.e, before all of the Bullers left that village).

The answer is easy to see: Heinrich 17 was born 14 March 1817 in Brenkenhoffswalde, which means that the Bullers did not move to Deutsch-Wymysle until sometime after that day. The time range of 1817–1826 is still rather large, but it is half what we started with. The other Deutsch-Wymysle lists that we will survey will no doubt narrow that gap further. Who knows? Maybe we will even be able to identify the very year the Brenkhoffswalde Bullers made the move.

Thursday, June 30, 2016

Wednesday, June 29, 2016

Bullers in Deutsch-Wymysle 2

The previous post surveyed the first list of interest in Robert Foth’s copy of records from the Deutsch-Wymysle congregation: a register of all those people who moved to the church from some other place. Focusing on the Bullers listed, we noticed, among other things, that:

We begin with the earliest Bullers born in Brenkenhoffswalde, according to the Deutsch-Wymysle records. There is a noteworthy gap between the first five Bullers (1799 and earlier) and the eleven who follow (all 1805 and after), which allows us to treat these five as probable members of the same generation. Listed in chronological order, these five Bullers are (numbers refer to the church-record numbers shown here):

Is it possible to say more about who these Bullers were? I think it is. If you recall, the land registers for Brenkenhoffswalde listed a number of Bullers. We began in 1767 with Peter Buller (351 in the Przechowka church book), then added his son Peter Jr. and a Heinrich Buller (whom we suggested could be a second son) in 1793. Peter Sr. (351) was gone by the 1805 and 1806 registers, but Peter Jr. and Heinrich remained. However, all Bullers were gone by the time of the 1826 Praestations-Tabel (land-tax list).

With full admission of the tentative nature of the suggestions that follow, let us see how we might reasonably arrange and make sense of these several strands of evidence. If it is correct to think that Peter Sr. (351) had an older son named Peter Jr. and a younger son named Heinrich, we can reason through the evidence as follows.

1. The 1793 land register lists Peter Jr. and Heinrich as lease holders. Obviously, the Heinrich and Peter listed in the Deutsch-Wymysle were too young (ages four and six) at that time to permit any sort of one-to-one identification between the two lists.

2. That being said, it is striking that both lists contain Bullers named Peter and Heinrich. Not to be missed is the fact that Peter is in the 1793 land list is presumably older than Heinrich (Peter was the firstborn, apparently, named after his father), whereas Heinrich in the Deutsch-Wymysle records is the older by two years.

3. Given the propensity of Mennonite males of that era to name their firstborn sons after themselves, one might expect Deutsch-Wymysle Heinrich’s father to have been named Heinrich as well. To state the matter differently, one would not expect a firstborn son named Heinrich to have been fathered by someone named Peter.

4. In light of all this, it is reasonable to think that Deutsch-Wymysle Heinrich was the firstborn son of Brenkenhoffswalde Heinrich, son of Peter Sr. (351). We certainly do not know this to be a fact, but it is a reasonable explanation of what we know (but see the second note below).

5. With this as a working hypothesis, we turn our attention to the identity of the next two Bullers in the table above: Peter 15 and Helene 16. Both were born Bullers, and they were married to each other (note the shared wedding date here). We can safely assume that they were not brother and sister, but it would not surprise if they were cousins, if one was the child of Peter Jr. and the other of Heinrich. As before, this is nothing more than an intriguing hypothesis awaiting further evidence.

6. We can say little about Tobias I and Kornelius. I do not recall seeing these first names used with Bullers before, although both were used with other Mennonite families in Brenkenhoffswalde (e.g., Tobias Sperling, Tobias Voot/Voth, Cornelius Vood/Voot/Voth).

7. Finally, it is worth noting that none of these Bullers shared a birth year, which is what one might expect from a small number of families (as few as two) having children. If there were four or five different families having children, it would be highly likely that some children would be born the same year. This observation is not dispositive in and of itself, but it is consistent with the picture we sketched out based on other evidence.

So, what might (!) we conclude? A reasonable working hypothesis is that (1) these five Bullers born in Brenkenhoffswalde were born into the only two families known to have lived in the village at this time: Peter Jr. and Heinrich, the two sons of Peter Buller 351; (2) the Heinrich Buller born in 1787 was the firstborn son of Heinrich son of Peter 351; (3) Peter born in 1789 and Helene of 1790 were cousins who married (one a child of Peter Jr., the other of Heinrich son of Peter 351), which was not unusual in that setting; and (4) Tobias I and Kornelius were younger siblings in these two Brenkenhoffswalde Buller families.

There is much more that we can draw from the information recorded in this first Deutsch-Wymysle list, but this is enough for now. The following post will return to a question asked earlier, during our initial explorations of the Neumark Bullers.

Notes

* The known chronology works out well for Heinrich 1787 being the son of Heinrich son of Peter 351. As noted earlier, the 1767 register states that Peter 351 had two sons (and two daughters): Peter Jr. and, probably, Heinrich. That second son had to be born no later than 1767, so he would have been at least twenty when Heinrich 1787 was born, perhaps several years older. That would be a normal age for someone in that context to have had his first son, whom he would probably have given his own name. Again, this coherence proves nothing, but it is suggestive.

* We should not forget that Heinrich son of Peter 351 is thought to have fathered the illegitimate son of Helena Voth in 1833 or thereabouts (see here). Supposing that Heinrich son of Peter 351 was the father of Heinrich 1787 and of Heinrich the illegitimate child does raise several questions: When a child was born out of wedlock, who typically named it? (My hunch is that the mother or her family gave the name, but that is merely a hunch.) If the father, would he give the child the same name as had been given to a previous son who was still living? (I can imagine a father estranged from his first son might do so.) The story of Heinrich son of Peter 351 is not yet finished; we will have occasion to return to him again later on in our explorations of Deutsch-Wymysle.

- they were born between 1787 and 1817;

- almost all were born in Brenkenhoffswalde;

- they lived mostly in Deutsch-Wymysle; and

- most also died in the Deutsch-Wymysle area.

We begin with the earliest Bullers born in Brenkenhoffswalde, according to the Deutsch-Wymysle records. There is a noteworthy gap between the first five Bullers (1799 and earlier) and the eleven who follow (all 1805 and after), which allows us to treat these five as probable members of the same generation. Listed in chronological order, these five Bullers are (numbers refer to the church-record numbers shown here):

Number

| First Name | Date of Birth |

20

| Heinrich | 12 April 1787 |

15

| Peter | 21 August 1789 |

16

| Helene | 22 August 1790 |

26

| Tobias I | 25 August 1791 |

25

| Kornelius | 27 January 1799 |

Is it possible to say more about who these Bullers were? I think it is. If you recall, the land registers for Brenkenhoffswalde listed a number of Bullers. We began in 1767 with Peter Buller (351 in the Przechowka church book), then added his son Peter Jr. and a Heinrich Buller (whom we suggested could be a second son) in 1793. Peter Sr. (351) was gone by the 1805 and 1806 registers, but Peter Jr. and Heinrich remained. However, all Bullers were gone by the time of the 1826 Praestations-Tabel (land-tax list).

With full admission of the tentative nature of the suggestions that follow, let us see how we might reasonably arrange and make sense of these several strands of evidence. If it is correct to think that Peter Sr. (351) had an older son named Peter Jr. and a younger son named Heinrich, we can reason through the evidence as follows.

1. The 1793 land register lists Peter Jr. and Heinrich as lease holders. Obviously, the Heinrich and Peter listed in the Deutsch-Wymysle were too young (ages four and six) at that time to permit any sort of one-to-one identification between the two lists.

2. That being said, it is striking that both lists contain Bullers named Peter and Heinrich. Not to be missed is the fact that Peter is in the 1793 land list is presumably older than Heinrich (Peter was the firstborn, apparently, named after his father), whereas Heinrich in the Deutsch-Wymysle records is the older by two years.

3. Given the propensity of Mennonite males of that era to name their firstborn sons after themselves, one might expect Deutsch-Wymysle Heinrich’s father to have been named Heinrich as well. To state the matter differently, one would not expect a firstborn son named Heinrich to have been fathered by someone named Peter.

4. In light of all this, it is reasonable to think that Deutsch-Wymysle Heinrich was the firstborn son of Brenkenhoffswalde Heinrich, son of Peter Sr. (351). We certainly do not know this to be a fact, but it is a reasonable explanation of what we know (but see the second note below).

5. With this as a working hypothesis, we turn our attention to the identity of the next two Bullers in the table above: Peter 15 and Helene 16. Both were born Bullers, and they were married to each other (note the shared wedding date here). We can safely assume that they were not brother and sister, but it would not surprise if they were cousins, if one was the child of Peter Jr. and the other of Heinrich. As before, this is nothing more than an intriguing hypothesis awaiting further evidence.

6. We can say little about Tobias I and Kornelius. I do not recall seeing these first names used with Bullers before, although both were used with other Mennonite families in Brenkenhoffswalde (e.g., Tobias Sperling, Tobias Voot/Voth, Cornelius Vood/Voot/Voth).

7. Finally, it is worth noting that none of these Bullers shared a birth year, which is what one might expect from a small number of families (as few as two) having children. If there were four or five different families having children, it would be highly likely that some children would be born the same year. This observation is not dispositive in and of itself, but it is consistent with the picture we sketched out based on other evidence.

So, what might (!) we conclude? A reasonable working hypothesis is that (1) these five Bullers born in Brenkenhoffswalde were born into the only two families known to have lived in the village at this time: Peter Jr. and Heinrich, the two sons of Peter Buller 351; (2) the Heinrich Buller born in 1787 was the firstborn son of Heinrich son of Peter 351; (3) Peter born in 1789 and Helene of 1790 were cousins who married (one a child of Peter Jr., the other of Heinrich son of Peter 351), which was not unusual in that setting; and (4) Tobias I and Kornelius were younger siblings in these two Brenkenhoffswalde Buller families.

There is much more that we can draw from the information recorded in this first Deutsch-Wymysle list, but this is enough for now. The following post will return to a question asked earlier, during our initial explorations of the Neumark Bullers.

Notes

* The known chronology works out well for Heinrich 1787 being the son of Heinrich son of Peter 351. As noted earlier, the 1767 register states that Peter 351 had two sons (and two daughters): Peter Jr. and, probably, Heinrich. That second son had to be born no later than 1767, so he would have been at least twenty when Heinrich 1787 was born, perhaps several years older. That would be a normal age for someone in that context to have had his first son, whom he would probably have given his own name. Again, this coherence proves nothing, but it is suggestive.

* We should not forget that Heinrich son of Peter 351 is thought to have fathered the illegitimate son of Helena Voth in 1833 or thereabouts (see here). Supposing that Heinrich son of Peter 351 was the father of Heinrich 1787 and of Heinrich the illegitimate child does raise several questions: When a child was born out of wedlock, who typically named it? (My hunch is that the mother or her family gave the name, but that is merely a hunch.) If the father, would he give the child the same name as had been given to a previous son who was still living? (I can imagine a father estranged from his first son might do so.) The story of Heinrich son of Peter 351 is not yet finished; we will have occasion to return to him again later on in our explorations of Deutsch-Wymysle.

Tuesday, June 28, 2016

An intriguing find

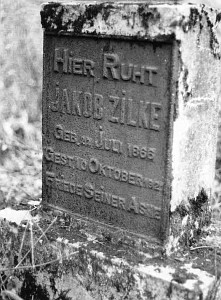

Even though most of our exploration involves scouring archives and records, every now and then a material artifact, some physical object, pops up and begs to be noticed. This happened last night with the Catalogue of Monuments of Dutch Colonization in Poland (here). While casually reading the descriptions of several villages near Deutsch-Wymysle and then examining the drawings and photographs that illustrate the text, a headstone from the Sady cemetery caught my eye. Can you see what is striking about this object?

Most of the text is clear:

To be clear, there is no reason to think that Jacob Zilke, born in 1865, was a direct relative of Helena, who died a decade before Jacob was born. However, given the fact that Sady was for a time home to a Mennonite population (it is unclear for how long), it is conceivable that Jacob Zilke had some sort of family connection to the Mennonite Helena Zielke who is one of our ancestors. At the very least, it is worth noticing and tucking away in case we encounter more information about the Zielke family.

Most of the text is clear:

Here lies (rests) so-and-so

Born 22 (?) July 1865

Died 10 October 1932

May his remains (ashes) rest in peace

The important part of all this is the identity of the so-and-so: Jacob Zilke. The last name is strikingly similar to that of Helena Zielke, wife of David Buller. In fact, given the variability of spellings at the time, one might reasonably think that the names are not merely similar but the same.Born 22 (?) July 1865

Died 10 October 1932

May his remains (ashes) rest in peace

To be clear, there is no reason to think that Jacob Zilke, born in 1865, was a direct relative of Helena, who died a decade before Jacob was born. However, given the fact that Sady was for a time home to a Mennonite population (it is unclear for how long), it is conceivable that Jacob Zilke had some sort of family connection to the Mennonite Helena Zielke who is one of our ancestors. At the very least, it is worth noticing and tucking away in case we encounter more information about the Zielke family.

Monday, June 27, 2016

Bullers in Deutsch-Wymysle 1

The evidence for Bullers in Deutsch-Wymysle stems primarily from a twentieth-century handwritten work known as “The History of the Mennonites of Deutsch-Wymysle, Poland” (Die Geschichte der Mennoniten zu Deutsch = Wymyschle - Polen). This work was composed by someone we met in the last post: Robert Foth. If you recall, Foth wrote the GAMEO article on Deutsch-Wymysle (see also Foth 1968), since he is frequently considered to be an authority on all things Deutsch-Wymysle: his family had been in the church for generations, and it is my impression that he was a member of the church up until the very end, that is, until the church closed in the mid-twentieth century. (Page scans of the Foth book are available here.)

Foth’s history of the church seems to incorporate material from the original church records, listing dates of birth, baptism, marriage, and death, as well as villages of birth and of residence and other information of genealogical interest. However, the information is not presented in a running list, as we have seen with the Przechowka church book. Rather, Foth’s history intersperses archival records with his story of the church’s history: he offers both data and interpretation.

Interesting as his narrative may be (e.g., he tells of the church’s experience of World War II from an apparently firsthand perspective), it is the records that are of most interest to us, so that is where our attention will be directed. Foth arranges these records in various forms, for example, a register of the Mennonites who moved to Deutsch-Wymysle from West Prussia and Neumark or a different list of Mennonites who left Deutsch-Wymysle for some other country (e.g., Russia, the United States).

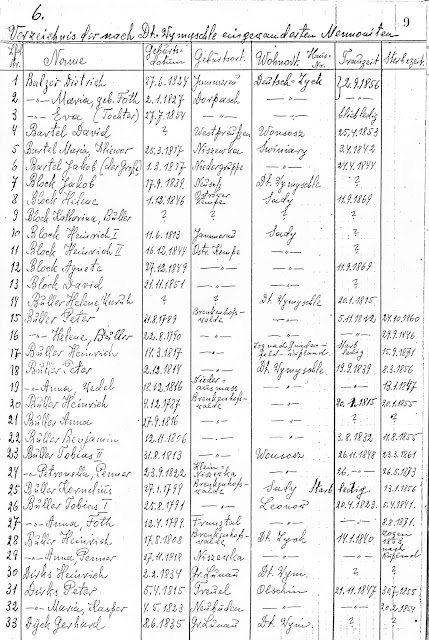

Each list deserves its own examination, so we begin with the first list in the book: Verzeichnis der nach Dt. Wymyschle eingewanderten Mennoniten aus Westpreußen und der Neumark (List of Mennonites Who Moved to Deutsch-Wymysle from West Prussia and Neumark). Seven pages list 234 persons in alphabetical order by last name (e.g., all the Balzers, followed by the Bartels, Blocks, Bullers, and so on).

We will make observations about the entire list a little later; for now our interest is with the Bullers in the church. Which Bullers moved to the Deutsch-Wymysle vicinity and joined the church there? The closeup of the scan below will provide all the answers.

Numbers 14–29 are Bullers either by birth or by marriage, sixteen in all (i.e., 6.8 percent of the 234 people listed). Since our interest is in Bullers by birth, we should exclude the five women who were Bullers by marriage: numbers 14, 19, 24, 27, and 29. This takes us down to eleven Bullers.

On the other hand, the list also contains six women who were born Buller but are now listed under a husband’s last name: (9) Katharina Buller Block, (93) Susanna Buller Kliewer, (126) Helene Buller Nachtigall, (127) Eva Buller Nachtigall (Helene and Eva were married to the same man), (162) Helene Buller Ratzlaff, and (209) Susanna Buller Unruh. This increases our total to seventeen Bullers by birth who moved to the church at Deutsch-Wymysle.

What can we observe about them?

1. The birth years recorded stretch from 1787 through 1817: 1787, 1789, 1790, 1781, 1799, 1805, 1806, 1808, 1809, 1813, 1814, 1815, 1816 (two), 1817, and two unknown. It would not be surprising if the four born earliest were parents of most or even all of the six born last (from 1813 on).

2. The place of birth is not known for two Bullers (9 and 162). Of the remaining fifteen, thirteen are said to have been born in Brenkenhoffswalde, the Mennonite village in the Neumark that captured our attention for a number of posts. The remaining two (126 and 127) were born in Ostrower Kämpe, a small village near the Przechowka church (F in the map here). Thus, until other evidence indicates otherwise, we can assume that the majority of the Bullers in the Deutsch-Wymysle church came from the Neumark village of Brenkenhoffswalde.

3. The primary village of residence is unknown for the same two Bullers (9 and 162) whose place of birth was unknown. Most of the remaining Bullers lived in Deutsch-Wymysle itself: 15, 16, 18, 20, 21, 22, 28, 93, and 209. However, some lived in one of the other small villages nearby: Wonsosz, Sady, Leonow, and Deutsch Zyck. What united them was their membership in the same Mennonite church, which was located in Deutsch-Wymysle.

4. The listing of a precise date of death would lead one to think that a person remained in the church all of his or her life. This notion may be supported by the explanatory notes provided when no date of death is given. For example, Heinrich Buller 28 and his wife Anna Penner Buller 29 do not have dates of death listed, only the note: moved to Russia in 1858 (Zogen 1858 nach Russland). So also Eva Buller Nachtigall 127 and Susanna Buller Unruh 2090 lack dates of death and are reported to have moved to Russia. This explanation makes sense, although one should also note one exception: Heinrich Buller 17 is said to have moved to Gnadenfeld (in Molotschna colony) and died unmarried, and his date of death is given. Nevertheless, for the most part it seems safe to think that the Bullers recorded with a date of death and no further indication of leaving probably lived out their days in the Deutsch-Wymysle area.

5. Speaking of dates of death, they range from 1838 (Helene Buller Nachtigall 126, who died at the age of twenty-nine) through 1871 (Heinrich 17 in Gnadenfeld): 1838, 1841, 1846, 1855 (two), 1856 (two), 1860, 1861, 1871, and four unknown.

6. It is easy enough to identify married couples (they share the same date of marriage): 15 + 16, 18 + 19, 23 + 24, 26 + 27, and 28 + 29. Two Bullers are listed as never married: Heinrich 17 and Kornelius 25; in both cases the marriage slot contains the note that they died unmarried (starb ledig). Finally, one wonders if Heinrich 20 has a marriage date listed but no spouse because his wife passed away before he moved from Brenkenhoffswalde to Deutsch-Wymysle. This explanation does not work for Benjamin 22 (he was married after leaving Brenkenshoffswalde), so his listing of a marriage date but no spouse must remain a mystery for the present.

We seemed to have mined this vein as completely as we can for the time being, so the next post or two will draw some conclusions from this data for our developing history of the larger Buller family, as well as for our understanding of the Deutsch-Wymysle church in general.

Works Cited

The Cemetery of Nowe Wymyśle. Page in the UpstreamVistula.org website. For additional pictures, background information, and further bibliography, see here.

Foth, Robert. 1968. Aufzeichnungen über das Leben der Mennoniten- und MB-Gemeinde zu Wymyschle, Polen. Mennonitische Rundschau 29 May.

Foth’s history of the church seems to incorporate material from the original church records, listing dates of birth, baptism, marriage, and death, as well as villages of birth and of residence and other information of genealogical interest. However, the information is not presented in a running list, as we have seen with the Przechowka church book. Rather, Foth’s history intersperses archival records with his story of the church’s history: he offers both data and interpretation.

Interesting as his narrative may be (e.g., he tells of the church’s experience of World War II from an apparently firsthand perspective), it is the records that are of most interest to us, so that is where our attention will be directed. Foth arranges these records in various forms, for example, a register of the Mennonites who moved to Deutsch-Wymysle from West Prussia and Neumark or a different list of Mennonites who left Deutsch-Wymysle for some other country (e.g., Russia, the United States).

Each list deserves its own examination, so we begin with the first list in the book: Verzeichnis der nach Dt. Wymyschle eingewanderten Mennoniten aus Westpreußen und der Neumark (List of Mennonites Who Moved to Deutsch-Wymysle from West Prussia and Neumark). Seven pages list 234 persons in alphabetical order by last name (e.g., all the Balzers, followed by the Bartels, Blocks, Bullers, and so on).

|

| Foth’s History of the Mennonites of Deutsch-Wymysle, Poland, page 9. |

We will make observations about the entire list a little later; for now our interest is with the Bullers in the church. Which Bullers moved to the Deutsch-Wymysle vicinity and joined the church there? The closeup of the scan below will provide all the answers.

Numbers 14–29 are Bullers either by birth or by marriage, sixteen in all (i.e., 6.8 percent of the 234 people listed). Since our interest is in Bullers by birth, we should exclude the five women who were Bullers by marriage: numbers 14, 19, 24, 27, and 29. This takes us down to eleven Bullers.

On the other hand, the list also contains six women who were born Buller but are now listed under a husband’s last name: (9) Katharina Buller Block, (93) Susanna Buller Kliewer, (126) Helene Buller Nachtigall, (127) Eva Buller Nachtigall (Helene and Eva were married to the same man), (162) Helene Buller Ratzlaff, and (209) Susanna Buller Unruh. This increases our total to seventeen Bullers by birth who moved to the church at Deutsch-Wymysle.

What can we observe about them?

1. The birth years recorded stretch from 1787 through 1817: 1787, 1789, 1790, 1781, 1799, 1805, 1806, 1808, 1809, 1813, 1814, 1815, 1816 (two), 1817, and two unknown. It would not be surprising if the four born earliest were parents of most or even all of the six born last (from 1813 on).

2. The place of birth is not known for two Bullers (9 and 162). Of the remaining fifteen, thirteen are said to have been born in Brenkenhoffswalde, the Mennonite village in the Neumark that captured our attention for a number of posts. The remaining two (126 and 127) were born in Ostrower Kämpe, a small village near the Przechowka church (F in the map here). Thus, until other evidence indicates otherwise, we can assume that the majority of the Bullers in the Deutsch-Wymysle church came from the Neumark village of Brenkenhoffswalde.

3. The primary village of residence is unknown for the same two Bullers (9 and 162) whose place of birth was unknown. Most of the remaining Bullers lived in Deutsch-Wymysle itself: 15, 16, 18, 20, 21, 22, 28, 93, and 209. However, some lived in one of the other small villages nearby: Wonsosz, Sady, Leonow, and Deutsch Zyck. What united them was their membership in the same Mennonite church, which was located in Deutsch-Wymysle.

|

| Fragment of a wooden cross in the Deutsch-Wymysle cemetery. Photograph by Jutta Dennerlein, 2005 (here). |

5. Speaking of dates of death, they range from 1838 (Helene Buller Nachtigall 126, who died at the age of twenty-nine) through 1871 (Heinrich 17 in Gnadenfeld): 1838, 1841, 1846, 1855 (two), 1856 (two), 1860, 1861, 1871, and four unknown.

6. It is easy enough to identify married couples (they share the same date of marriage): 15 + 16, 18 + 19, 23 + 24, 26 + 27, and 28 + 29. Two Bullers are listed as never married: Heinrich 17 and Kornelius 25; in both cases the marriage slot contains the note that they died unmarried (starb ledig). Finally, one wonders if Heinrich 20 has a marriage date listed but no spouse because his wife passed away before he moved from Brenkenhoffswalde to Deutsch-Wymysle. This explanation does not work for Benjamin 22 (he was married after leaving Brenkenshoffswalde), so his listing of a marriage date but no spouse must remain a mystery for the present.

We seemed to have mined this vein as completely as we can for the time being, so the next post or two will draw some conclusions from this data for our developing history of the larger Buller family, as well as for our understanding of the Deutsch-Wymysle church in general.

Works Cited

The Cemetery of Nowe Wymyśle. Page in the UpstreamVistula.org website. For additional pictures, background information, and further bibliography, see here.

Foth, Robert. 1968. Aufzeichnungen über das Leben der Mennoniten- und MB-Gemeinde zu Wymyschle, Polen. Mennonitische Rundschau 29 May.

Saturday, June 25, 2016

Deutsch-Wymysle 1

Now that we have laid a proper historical and social background to Mennonite settlement in Poland as one element of a larger colonization and reclamation project undertaken by the Olędrzy, we are ready to focus our attention on a particular village in which some Bullers lived and died and were buried: Deutsch-Wymysle.

As previously noted, the village was in the historical Polish region known as Mazovia (or Masovia; Polish: Mazowsze); the location of Deutsch-Wymysle in Mazovia is indicated by the asterisk in the map below. We might also notice the general location of the Schwetz/Przechowka community, which was in an adjoining region known as Kujawy (or Kuyavia); the asterisk above “Kuyavia” provides the approximate location of that Mennonite center.

According to some authorities, there was a close relation between the Przechowka church and the one established later at Deutsch-Wymysle (modern Nowe Wymyśle). For example, Robert Foth writes:

Peter J. Klassen offers a similar account:

Others, however, tell a different story. According to the Nowe Wymyśle entry in the Catalogue of Monuments of Dutch Colonization in Poland (see here),

There really is no reconciling the two histories of the founding of the village: one version states that Mennonite groups founded the village and congregation in the early 1760s; the other reports that the village was founded in 1781 by a particular individual* and initially settled by five German Lutheran families; it was only later that the Mennonites settled in the already-established village and formed a new congregation there.

We will return to the question of the founding of Deutsch-Wymysle as time and abilities permit. For now let me say simply that the better evidence and arguments seem to come from the second explanation. Robert Foth, the main advocate of the first version, is clearly familiar with Deutsch-Wymysle: his family lived there, and he has provided the copy of the church records that we will begin exploring in future posts. That being said, his view seems to rest more on the oral tradition passed on over the last two centuries than on documentary evidence.

The attribution of Deutsch-Wymysle’s founding to the Polish noble Kajeten Dębowski and German Lutheran Olędrzy (see here), on the other hand, appears better supported by the historical record, as argued by Wojciech Marchlewski (1986) and Erich L. Ratzlaff (1971). In the first place, an argument that names the actual individuals involved is more compelling than one that refers vaguely to certain groups performing the same actions. This explanation is also supported by contemporary government documents and comports well with what we learned of the Olędrzy: it is perfectly reasonable that one group of Olędrzy (German Lutherans, or Evangelicals, as they are often called) founded the village and reclaimed the land, then sold the leases to another group of Olędrzy, namely, Mennonites, which included some Bullers. These Mennonites may have entered the area and purchased leases gradually over the course of several decades, which would account for a community memory of being in the area from the beginning, so to speak; nevertheless, we should not confuse Mennonite presence with a Mennonite founding of the village or the establishment of a church in the eighteenth century.

Why raise this question now? As we look at the record of Bullers and other Mennonites in Deutsch-Wymysle, we should ask if the evidence tilts us toward one explanation or another as to the founding of Deutsch-Wymysle and the first Mennonite presence there.

Note

* Apparently Kajeten Dębowski was the Polish noble who owned the land; he leased it to the five named Olędrzy for development.

Works Cited

Foth, Robert. 1956. Deutsch-Wymysle (Masovian Voivodeship, Poland). Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1956. Available online here.

Klassen, Peter J. 2009. Mennonites in Early Modern Poland and Prussia. Young Center Books in Anabaptist and Pietist Studies. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Marchlewski, Wojciech. 1986. Mennonici w Polsce (o powstaniu społeczności mennonitów Wymyśla Nowego) [The Mennonites in Poland (The Origins of the Mennonite Community in Wymyśle Nowe)]. Etnografia Polska 30:129–46. Available online here.

Ratzlaff, Erich L. 1971. Im Weichselbogen: Mennonitensiedlungen in Zentralpolen. Winnipeg: Christian Press.

As previously noted, the village was in the historical Polish region known as Mazovia (or Masovia; Polish: Mazowsze); the location of Deutsch-Wymysle in Mazovia is indicated by the asterisk in the map below. We might also notice the general location of the Schwetz/Przechowka community, which was in an adjoining region known as Kujawy (or Kuyavia); the asterisk above “Kuyavia” provides the approximate location of that Mennonite center.

|

| Map modified from original created by Winnetou14. See further here. |

In 1762 Mennonite emigrants from the West Prussian congregations of Przechovka near Schwetz and of Montau-Gruppe near Graudenz made their way upstream into Poland and settled in the province of Warsaw, district Gostynin, not far from the town of Gombin (Gabin), and founded the Deutsch-Wymysle village and congregation. In 1764 a second group arrived from Przechovka.

Peter J. Klassen offers a similar account:

Farther up the river from Thorn, not far from the city of Plock, another congregation developed, with members from a number of nearby villages. This church was located in Deutsch (Nowe) Wymyśle. In the 1760s some Mennonite families emigrated here from Przechówka, the Gruppe-Montau region, and elsewhere, and established a new congregation in Wymyśle. (2009, 95)

Others, however, tell a different story. According to the Nowe Wymyśle entry in the Catalogue of Monuments of Dutch Colonization in Poland (see here),

The village was founded by Kajeten Dębowski in 1781 and was settled by: Jakub Konarski, Jerzy Drews, Jan Konarski, Jan Goln, and Dawid Górski. Under the agreement, the colonists undertook to clear the forest on the assigned area (half a włóka per colonist [roughly 22 acres]). They were granted a 7 year rent-free period in exchange. After the land had been cleared, its acreage was measured in order to determine the settlers’ duties. The contract also provided for extensive legal and governmental autonomy. They were under the direct judicial authority of the district courts and were outside of the landowners’ jurisdiction.

Although the village initially was settled by the Evangelical [i.e., German Lutheran] colonists it constituted one of the three most important Mennonite centers in Mazowsze for many decades. The Mennonite community was established in 1813 by settlers who moved here from villages located near the Vistula (e.g. Sady).

Although the village initially was settled by the Evangelical [i.e., German Lutheran] colonists it constituted one of the three most important Mennonite centers in Mazowsze for many decades. The Mennonite community was established in 1813 by settlers who moved here from villages located near the Vistula (e.g. Sady).

|

| Aerial view of modern Nowe Wymyśle. |

We will return to the question of the founding of Deutsch-Wymysle as time and abilities permit. For now let me say simply that the better evidence and arguments seem to come from the second explanation. Robert Foth, the main advocate of the first version, is clearly familiar with Deutsch-Wymysle: his family lived there, and he has provided the copy of the church records that we will begin exploring in future posts. That being said, his view seems to rest more on the oral tradition passed on over the last two centuries than on documentary evidence.

The attribution of Deutsch-Wymysle’s founding to the Polish noble Kajeten Dębowski and German Lutheran Olędrzy (see here), on the other hand, appears better supported by the historical record, as argued by Wojciech Marchlewski (1986) and Erich L. Ratzlaff (1971). In the first place, an argument that names the actual individuals involved is more compelling than one that refers vaguely to certain groups performing the same actions. This explanation is also supported by contemporary government documents and comports well with what we learned of the Olędrzy: it is perfectly reasonable that one group of Olędrzy (German Lutherans, or Evangelicals, as they are often called) founded the village and reclaimed the land, then sold the leases to another group of Olędrzy, namely, Mennonites, which included some Bullers. These Mennonites may have entered the area and purchased leases gradually over the course of several decades, which would account for a community memory of being in the area from the beginning, so to speak; nevertheless, we should not confuse Mennonite presence with a Mennonite founding of the village or the establishment of a church in the eighteenth century.

Why raise this question now? As we look at the record of Bullers and other Mennonites in Deutsch-Wymysle, we should ask if the evidence tilts us toward one explanation or another as to the founding of Deutsch-Wymysle and the first Mennonite presence there.

Note

* Apparently Kajeten Dębowski was the Polish noble who owned the land; he leased it to the five named Olędrzy for development.

Works Cited

Foth, Robert. 1956. Deutsch-Wymysle (Masovian Voivodeship, Poland). Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1956. Available online here.

Klassen, Peter J. 2009. Mennonites in Early Modern Poland and Prussia. Young Center Books in Anabaptist and Pietist Studies. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Ratzlaff, Erich L. 1971. Im Weichselbogen: Mennonitensiedlungen in Zentralpolen. Winnipeg: Christian Press.

Friday, June 24, 2016

Who were the Olędrzy?

Although we planned to narrow our focus to the single village Deutsch-Wymysle, it seems best, upon reflection, to keep our field of vision wide for at least one more post. The context will prove helpful in the long run as we weigh competing claims about who actually founded Deutsch-Wymysle in the first place.

The plural term “Olędrzy” in the post title is a new one, but its singular form (Olęder) and variations (also Holenders or Holęder; German: Holländer or Hauländer) hints at its meaning: it has something to do with people from Holland. In fact, the Olędrzy were people who emigrated to Poland and lived in villages “organized under a particular type of law” (here).

The law under which they were organized is by now familiar to us: they enjoyed personal freedom (they were not serfs), community self-government, the granting of long-term (typically forty years) leases to the land, and the right to pass on the rights of the lease to heirs. As one might expect, Dutch Mennonites constituted a sizable percentage of the early Olędrzy, but we should not mistakenly think that all Olędrzy were Mennonites.

This was especially true as time went on, and eventually the term came to be applied to any group of colonists, regardless of their ethnicity, who lived and worked as the earliest Oledrzy had done. So it was that many Germans and Poles, as well as some Hungarians, Czechs, and Scots, also settled in Poland and enjoyed the privileges of the law first extended to the original Dutch Olędrzy. From the beginning of Olęder immigration in the 1500s through 1864, at least 1,700 Olęder villages were established;* only 300 were settled by ethnic Dutch (here), which gives a good sense of how the ethnic composition of the Olędrzy shifted over the centuries.

The original Olędrzy were welcomed into Poland for a simple reason: to turn unprofitable riverland into productive farmland. Jerzy Szaùygin writes:

The means by which the original Dutch and then their heirs reclaimed the land will be the subject of another post. For now we end by emphasizing several important points.

1. When the colonists of Poland are identified as Olędrzy or “the Dutch,” one should not assume that the colonists’ ethnic background is in view. Especially for the mid-eighteenth century on, the term is more probably a reference to a specific legal status and way of life, that of free people reclaiming and farming land from Poland’s river bottoms.

2. Although all Mennonites were Olędrzy (speaking loosely), not all Olędrzy were Mennonites. In fact, the largest numbers of Olędrzy in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries apparently were German Lutherans, often called “Evangelicals” in the literature. Naturally, the Mennonites typically lived in their villages and the Lutherans in theirs, but both were considered part of the Olędrzy class.

All of this background, but especially these final observations, will be helpful as we finally turn our attention to the village of Deutsch-Wymysle in the following post.

Note

* Nearly two hundred Olęder settlements were established in the Mazovia (Mazowsze) region; this ratio (200/1,700) offers evidence that Olęder settlement was a widespread phenomenon throughout Poland, not merely a regional development.

Works Cited

Olędrzy. Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. Available online here.

Szaùygin, Jerzy. Introduction to Catalogue of Monuments of Dutch Colonization in Poland. Available online here or here.

The plural term “Olędrzy” in the post title is a new one, but its singular form (Olęder) and variations (also Holenders or Holęder; German: Holländer or Hauländer) hints at its meaning: it has something to do with people from Holland. In fact, the Olędrzy were people who emigrated to Poland and lived in villages “organized under a particular type of law” (here).

|

| A typical Olędrzy house, this one built between 1800 and 1825. |

This was especially true as time went on, and eventually the term came to be applied to any group of colonists, regardless of their ethnicity, who lived and worked as the earliest Oledrzy had done. So it was that many Germans and Poles, as well as some Hungarians, Czechs, and Scots, also settled in Poland and enjoyed the privileges of the law first extended to the original Dutch Olędrzy. From the beginning of Olęder immigration in the 1500s through 1864, at least 1,700 Olęder villages were established;* only 300 were settled by ethnic Dutch (here), which gives a good sense of how the ethnic composition of the Olędrzy shifted over the centuries.

The original Olędrzy were welcomed into Poland for a simple reason: to turn unprofitable riverland into productive farmland. Jerzy Szaùygin writes:

They were always settled either along rivers, or in lowland and marshy areas. Due to their centuries-old experience in fighting the floods in their native country, the colonists were able to turn barren land, seemingly unsuitable for cultivation, into a state of flourishing agriculture. They achieved this by establishing a complex system of channels, dams, and weirs. Based on cattle-raising and fruit farming, their agriculture was characterized by good work organization, and was much more advanced and productive than that of the local serfs. Therefore, the colonization of the previously uncultivated land was of great benefit to the local landowners.

The means by which the original Dutch and then their heirs reclaimed the land will be the subject of another post. For now we end by emphasizing several important points.

1. When the colonists of Poland are identified as Olędrzy or “the Dutch,” one should not assume that the colonists’ ethnic background is in view. Especially for the mid-eighteenth century on, the term is more probably a reference to a specific legal status and way of life, that of free people reclaiming and farming land from Poland’s river bottoms.

2. Although all Mennonites were Olędrzy (speaking loosely), not all Olędrzy were Mennonites. In fact, the largest numbers of Olędrzy in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries apparently were German Lutherans, often called “Evangelicals” in the literature. Naturally, the Mennonites typically lived in their villages and the Lutherans in theirs, but both were considered part of the Olędrzy class.

All of this background, but especially these final observations, will be helpful as we finally turn our attention to the village of Deutsch-Wymysle in the following post.

Note

* Nearly two hundred Olęder settlements were established in the Mazovia (Mazowsze) region; this ratio (200/1,700) offers evidence that Olęder settlement was a widespread phenomenon throughout Poland, not merely a regional development.

Olędrzy. Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. Available online here.

Szaùygin, Jerzy. Introduction to Catalogue of Monuments of Dutch Colonization in Poland. Available online here or here.

Wednesday, June 22, 2016

New territory

Buller Time continues to explore new territory, both geographically and genealogically, in search of not only our own direct ancestors but any Buller who forms part of our larger family. Over the past few years we have traveled back from Lushton, Nebraska, to the high plains of south Russia (modern Ukraine), to a Mennonite colony known as Molotschna. There that we learned not only of the village life that David and Peter D enjoyed but also of the land crisis that prompted Peter and Sarah to lead their family to a new life in a new world.

From Molotschna and its villages we took another step back in time and traveled to the northwest, to the historical region known as Volhynia, where David and his now-found father and mother Benjamin and Helena lived early in the nineteenth century.

Learning there that Volhynian Mennonites typically came from either the Schwetz area of Poland or the Neumark region of Prussia, we invested considerable time exploring those two locales. We returned time and again to the Mennonite church at Przechowka, a few miles southwest of Schwetz, and especially to its church book that records so many of our family’s names.

Most recently we spent considerable time in the Neumark (aka Netzebruch, Driesen, Brandenburg) villages of Neu Dessau, Brenkenhoffswalde, and Franztal, tracing several Bullers from there back to Schwetz and others forward to Volhynia. Having extracted all we can from that mine of information, it is time to move on to a new locale.

From the villages of Neumark (located only 100 miles east of Berlin, Germany) we travel 160 miles to the east–southeast and back into Poland. Warsaw lies along the Vistula only 50 miles further to the southeast. The village that interests us is Deutsch-Wymysle (modern Nowe Wymyśle), a Mennonite outpost in the early nineteenth century.

We will take plenty of time to learn about the area and especially the Bullers who lived there (this was the village, after all, into which Karl Buller was born in 1826), but for now a few general observations will suffice.

First, the spread of the Mennonite presence in Poland was from north to south and primarily along the Vistula River. The earliest Mennonites in Poland, we have seen, settled around Danzig (Gdańsk) and then into the large delta where the Vistula and its tributaries emptied into the Baltic Sea. It was here that most Dutch Mennonites (none of our family, as far as we know) made their mark by draining the lowlands around the river and turning it into productive farmland. From that time on Mennonites, as well as other groups (more on that in a future post), moved steadily upstream and did the same with the lowlands on both sides of the Vistula.

Why is this important to notice? It was only natural that various Mennonite groups, including Bullers, moved farther upstream and established Deutsch-Wymysle. The Schwetz and Torun areas were now being farmed, but virgin territory remained to be put into production. Simply stated, the move to this new area to found a new village was simply a matter of going where work remained to be done.

Second, this move led our family to a new area in Poland: Mazovia (Polish: Mazowsze). The modern Mazovian Voivodeship (i.e., province) corresponds roughly to the historical area with which we are concerned. As a result of the late eighteenth-century partitions of Poland, the greater part of Mazovia was incorporated into the Prussian Empire.

Prussian domination was short-lived, however, and in 1807 Mazovia became part of the Duchy of Warsaw, which was a Polish state Napoleon established after he had defeated the Prussians. Even this was not the end of the matter. Eight years later Mazovia became part of the Congress Kingdom of Poland, a state that was allied with, dependent on, and ultimately absorbed into the Russian Empire.

As we explore the life of Bullers in Mazovia further, it will be important to keep in mind not only the geographical setting (upstream from Schwetz along the Vistula) but also the historical context (a time of power shifts from Poland to Prussia to Poland to Russia) in which our ancestors lived, since both their lives and their journeys were no doubt influenced by the political changes taking place all around them. These Mennonites may have lived as the “quiet in the land” (a favored Mennonite self-designation), but the land itself was anything but quiet during these tumultuous times.

With that as a broad and general background, we are ready to narrow our focus onto the village in which we will next find Bullers: Deutsch-Wymysle, on the south side of the Vistula River.

From Molotschna and its villages we took another step back in time and traveled to the northwest, to the historical region known as Volhynia, where David and his now-found father and mother Benjamin and Helena lived early in the nineteenth century.

Learning there that Volhynian Mennonites typically came from either the Schwetz area of Poland or the Neumark region of Prussia, we invested considerable time exploring those two locales. We returned time and again to the Mennonite church at Przechowka, a few miles southwest of Schwetz, and especially to its church book that records so many of our family’s names.

Most recently we spent considerable time in the Neumark (aka Netzebruch, Driesen, Brandenburg) villages of Neu Dessau, Brenkenhoffswalde, and Franztal, tracing several Bullers from there back to Schwetz and others forward to Volhynia. Having extracted all we can from that mine of information, it is time to move on to a new locale.

|

| From (1) Molotschna we moved northwest to (2) Volhynia, whose Mennonite residents came largely from (3) the Schwetz (Przechowka) area and (4) the Neumark region. |

From the villages of Neumark (located only 100 miles east of Berlin, Germany) we travel 160 miles to the east–southeast and back into Poland. Warsaw lies along the Vistula only 50 miles further to the southeast. The village that interests us is Deutsch-Wymysle (modern Nowe Wymyśle), a Mennonite outpost in the early nineteenth century.

|

| Schwetz/Przechowka is in the upper left, Deutsch-Wymysle is the red pin in the lower center, circa 85 miles to the south–southeast. |

We will take plenty of time to learn about the area and especially the Bullers who lived there (this was the village, after all, into which Karl Buller was born in 1826), but for now a few general observations will suffice.

First, the spread of the Mennonite presence in Poland was from north to south and primarily along the Vistula River. The earliest Mennonites in Poland, we have seen, settled around Danzig (Gdańsk) and then into the large delta where the Vistula and its tributaries emptied into the Baltic Sea. It was here that most Dutch Mennonites (none of our family, as far as we know) made their mark by draining the lowlands around the river and turning it into productive farmland. From that time on Mennonites, as well as other groups (more on that in a future post), moved steadily upstream and did the same with the lowlands on both sides of the Vistula.

Why is this important to notice? It was only natural that various Mennonite groups, including Bullers, moved farther upstream and established Deutsch-Wymysle. The Schwetz and Torun areas were now being farmed, but virgin territory remained to be put into production. Simply stated, the move to this new area to found a new village was simply a matter of going where work remained to be done.

Second, this move led our family to a new area in Poland: Mazovia (Polish: Mazowsze). The modern Mazovian Voivodeship (i.e., province) corresponds roughly to the historical area with which we are concerned. As a result of the late eighteenth-century partitions of Poland, the greater part of Mazovia was incorporated into the Prussian Empire.

Prussian domination was short-lived, however, and in 1807 Mazovia became part of the Duchy of Warsaw, which was a Polish state Napoleon established after he had defeated the Prussians. Even this was not the end of the matter. Eight years later Mazovia became part of the Congress Kingdom of Poland, a state that was allied with, dependent on, and ultimately absorbed into the Russian Empire.

As we explore the life of Bullers in Mazovia further, it will be important to keep in mind not only the geographical setting (upstream from Schwetz along the Vistula) but also the historical context (a time of power shifts from Poland to Prussia to Poland to Russia) in which our ancestors lived, since both their lives and their journeys were no doubt influenced by the political changes taking place all around them. These Mennonites may have lived as the “quiet in the land” (a favored Mennonite self-designation), but the land itself was anything but quiet during these tumultuous times.

With that as a broad and general background, we are ready to narrow our focus onto the village in which we will next find Bullers: Deutsch-Wymysle, on the south side of the Vistula River.

Saturday, June 18, 2016

Who was the first?

Research does not have to be serious and focused all the time; on occasion it can be borderline frivolous and little more than fun, more akin to surfing the Web than engaging in sober study. For example, recently a question came to mind that prompted a fun bit of research: Who was the first Carl Buller?

We all know and love our family’s current Carl Buller (Happy Father’s Day, Dad!), but who was the first? There is only one place to find the answer to that kind of question: the GRANDMA database—so off to the database I went. The answer was just a few clicks away.

Ignoring all the Bullers named Charles (GRANDMA returns alternate spellings if a searcher wants) and the Carls and Karls named Buhler or Buehler, it was easy to see that the earliest Carl/Karl Buller was GRANDMA number 28456. One click from the results screen, and we were at the page for Karl Buller 28456.

Foth, Robert. 1956. Deutsch-Wymysle (Masovian Voivodeship, Poland). Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Available online here.

We all know and love our family’s current Carl Buller (Happy Father’s Day, Dad!), but who was the first? There is only one place to find the answer to that kind of question: the GRANDMA database—so off to the database I went. The answer was just a few clicks away.

Born 10 March 1826 in Deutsch-Wymysle, Prussia, Karl was the son of Tobias and Anna Foth Buller. To put this in a more precise historical context, Karl Buller was nine years younger than David father of Peter D.

The reference to Deutsch-Wymysle, Prussia, was a new one, so I decided to explore further, beginning with Robert Foth’s 1956 article on the village in GAMEO. We will return to the village history and location later (a number of posts of interest to Bullers will arise out of this information); for now we jump ahead in the story to a twentieth-century handwritten copy of the original church records (which were apparently lost in a fire), which provides us additional details about Karl Buller 28456.

The reference to Deutsch-Wymysle, Prussia, was a new one, so I decided to explore further, beginning with Robert Foth’s 1956 article on the village in GAMEO. We will return to the village history and location later (a number of posts of interest to Bullers will arise out of this information); for now we jump ahead in the story to a twentieth-century handwritten copy of the original church records (which were apparently lost in a fire), which provides us additional details about Karl Buller 28456.

There listed plain as day is the first Karl (also the firstborn of his parents), born 10 March 1826 in the village of Deutsch-Wymysle and married (we know not to whom) on 14 August 1854. The last column records the place of his death, which is by now well known to all of us: Volhynia.

We have only scratched the surface of what lies waiting to be discovered in Deutsch-Wymysle (note, for example, where Karl’s parents were born), but it is enough for now. Sometimes even fun and frivolous research, such as a search for the first Carl/Karl Buller, leads us in unexpected and rewarding directions. That is certainly the case in this instance, so Buller Time will now leave Neumark behind (sort of) and move back into Poland in search of more pieces of the puzzle in our larger Buller family history.

We have only scratched the surface of what lies waiting to be discovered in Deutsch-Wymysle (note, for example, where Karl’s parents were born), but it is enough for now. Sometimes even fun and frivolous research, such as a search for the first Carl/Karl Buller, leads us in unexpected and rewarding directions. That is certainly the case in this instance, so Buller Time will now leave Neumark behind (sort of) and move back into Poland in search of more pieces of the puzzle in our larger Buller family history.

Work Cited

Foth, Robert. 1956. Deutsch-Wymysle (Masovian Voivodeship, Poland). Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Available online here.

Happy belated birthday, Buller Time!

Better late than never, I would like to note for Buller Time’s tens (ha!) of readers the recently passed second birthday of the blog. The first two posts were made on 15 June 2014 and consisted primarily of two pictures: a Mennonite barn in Molotschna colony (here) and the nineteenth-century windmill located on the outskirts of Alexanderkrone, where Peter D and family lived for a few years (here).

All told, Buller Time has published 291 posts—in spite of the great hiatus of 2015. Thanks to all who show interest and support by visiting and reading and occasionally (!) commenting. According to Blogger, Buller Time has been visited 15,373 times since its launch. My own daily records show that around 25 people visit each day. Not bad for a bunch of often-landless hicks from Switzerland (?) by way of Poland and Volhynia and Molotschna and Lushton!

Thanks most of all to our ancestors, especially Grandpa Chris and Grandma Malinda, who not only gave us all life but also inspired the creation of this blog.

All told, Buller Time has published 291 posts—in spite of the great hiatus of 2015. Thanks to all who show interest and support by visiting and reading and occasionally (!) commenting. According to Blogger, Buller Time has been visited 15,373 times since its launch. My own daily records show that around 25 people visit each day. Not bad for a bunch of often-landless hicks from Switzerland (?) by way of Poland and Volhynia and Molotschna and Lushton!

Thanks most of all to our ancestors, especially Grandpa Chris and Grandma Malinda, who not only gave us all life but also inspired the creation of this blog.

Friday, June 17, 2016

Mennonites in Neumark 3

The first posts in this mini-series addressed when and why Mennonites moved to the Neumark (aka Netzebruch, Driesen, Brandenburg) area, as well as what life, especially church life, was like for the Bullers and other families who populated the villages of Fraztal and Brenkenhoffswalde. This final post looks to the end of Mennonite habitation in the region, in an attempt to understand why so many families left in the early decades of the 1800s, culminating in the exodus of nearly all Mennonites in 1834.

As is so often the case, historical context helps us understand our ancestors’ lives and choices. Surprisingly enough, our story begins with Napoleon. As the History Channel so capably summarizes (here), Napoleon was a French military officer during the time of the French Revolution (1789–1799) who rose through the ranks far beyond his peers until he was appointed commander of the entire military in 1796. Three years later he engineered a coup that set him at the top of the French Republic. Eventually, in 1804, the Senate declared him Emperor of the French.

Even when he was fighting on behalf of the revolution, Napoleon sought to conquer territory far beyond what many would consider traditional French territory. Nothing changed in that regard when Napoleon became emperor. If anything, his quest to expand French control only increased.

Of course, the other powers and nations of the day did not wish to serve a French emperor, so both individually and, more often, in alliance they battled Napoleon wherever his armies sought to go. The coalition that interests us most is the fourth, which included Britain, Prussia, Russia, Saxony, and Sweden and spanned the years 1806–1807.

What is of most interest to Mennonites and us Bullers happened during these years. In August 1806 the Prussian king Frederick William III, for reasons not entirely understood, went to war against Napoleon all on his own, with no help from his coalition partners or his military ally Russia. The results were devastating. In the space of nineteen days the Prussian army of 250,000 was literally decimated through the deaths of 10 percent of its soldiers; another 150,000 were taken as prisoners, as well as 4,000 artillery pieces and over 100,000 muskets (see here).

Not only was the Prussian army destroyed completely as an effective fighting force, but Napoleon also added Prussian territory to his realm. The effect of all this on the psyche of the Prussian/German people was devastating, and it prompted the Prussians, after Napoleon’s advance was turned back and his power weakened by the Russians in 1812, to rebuild their offensive might as fully as possible and to add to that a second layer of military capability available for protecting Prussian home territory.

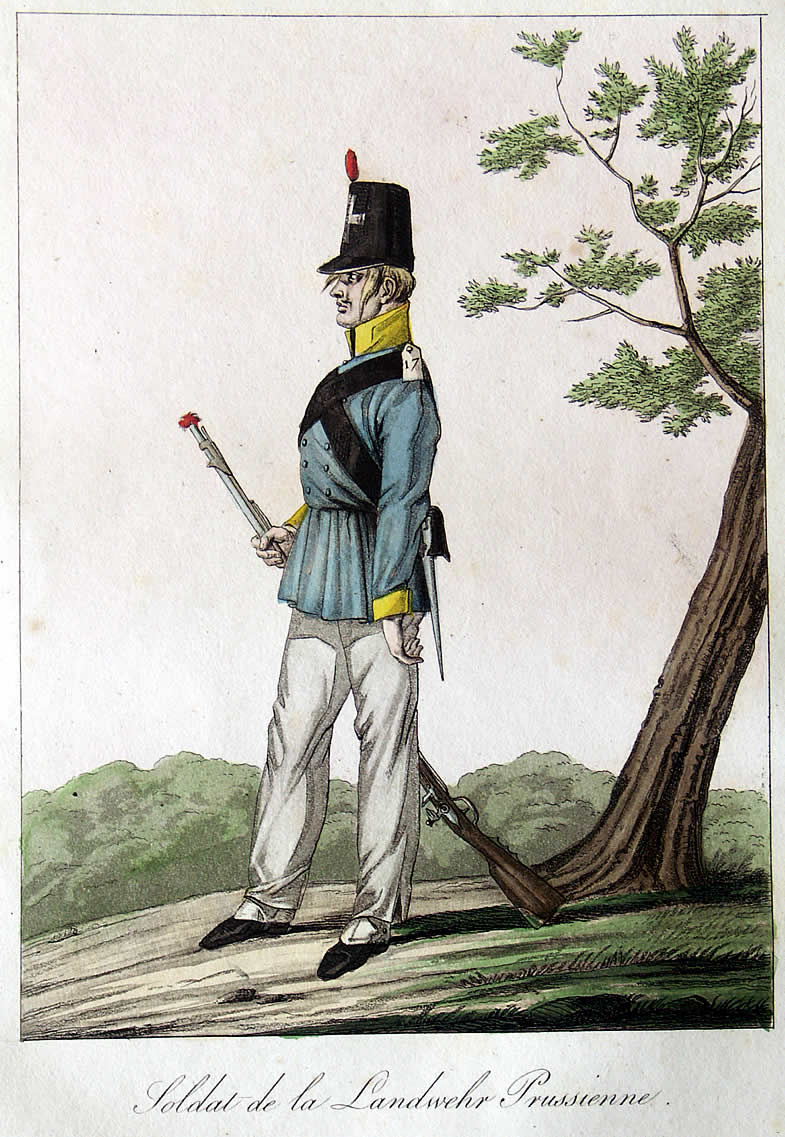

The means used to accomplish the latter was the Landwehr (literally, country defense) of 1813. This royal edict mandated that all males living in Prussia between the ages of eighteen and forty-five who were not already serving in the regular army were to be conscripted (drafted) into special units dedicated primarily to defending the homeland. The key thing to note here is that all males of this age were registered for service—including Mennonites.

As might be expected, the edict was enforced with different degrees of rigor in different regions and likewise encountered different Mennonite responses from place to place. Some government officials overlooked Mennonites who did not comply, while others sought to register every last male. Some Mennonites refused to be registered at all (even though registration did not automatically lead to military service), while others adhered to the law. Of interest to us is Adalbert Goertz’s record of registrations for the Schwetz district, which reveals that all males regardless of their age were registered, including Jacob Buller, 56; Heinrich Buller, 26; Jacob Buller, 9 (all from Przechowka); and Jacob Buller, 45 (Ostrowo Kämpe; see here, table 8).

Although it seems that only a few Mennonites actually saw action, and that generally voluntarily, the proverbial writing was on the wall. The long-standing exclusion of Mennonites from military service was slowly but surely eroding.

It is probably no coincidence that Mennonites—and Bullers—in the Neumark and the Schwetz areas began to immigrate east to Volhynia and Russia during the following several decades. Indeed, all but a handful of members of the Przechowka church moved to the Molotschna colony in 1819–1820 and 1823–1824. As we noted previously (here and here), all the Buller families likewise disappeared from the Neumark area between 1806 and 1826. The most reasonable explanation is found in the growing movement toward universal conscription (i.e., all males subject to the draft) within Prussia during this time. (There is no better account of this development than that found in Jantzen 2010.)

The Mennonites who left in the 1810s and 1820s were shown to have acted wisely in the early 1830s, which is when we take up the story with regard to Neumark (this is not to say that other Mennonite areas were unaffected; they were, but our concern is Neumark). On 16 May 1830, the Mennonite Edict of 1789, which previously had been operative only for the province of Prussia (not the entire Prussian kingdom), was extended to West Prussia (i.e., including Neumark and the Schwetz area) as well. Stated simply, this edict gave Mennonites a choice: serve in the military, like all other Prussians, or pay an extra tax and suffer the loss of some civil rights, including the right to buy land that was nonexempt (i.e., that carried the responsibility of military service).

The extension of the edict’s terms over the Neumark area met with stiff opposition, as “all forty-three heads of household [in Brenkenhoffswalde] went on record as rejecting the option of serving in the military” (Jantzen 2010, 115). When officials attempted to collect the additional taxes and to limit the sale of property according to the terms of the edict, the Mennonites appealed to Frederick William III to uphold the terms of their charter. Frederick “said that he would like to help the Mennonites, but he could not exempt them from the obligations borne by other citizens” (Klassen 2009, 87)

Over the course of the next few years, therefore, the Neumark Mennonite communities arranged to leave their home of seventy years behind. Elder Wilhelm Lange (here) negotiated permission with the Russian government for forty Mennonite families to emigrate to the Molotschna colony, and so it was that

As noted earlier (here), these “new attitudes” played a key role in the development of the Mennonite Brethren movement during the middle of the nineteenth century.

Although the spirit and values and descendants of the Neumark Mennonites lived on in Molotschna and far beyond, the community ceased to exist in 1834. There are no doubt Bullers buried in and around the villages of Neu Dessau, Franztal, and Brenkenhoffswalde. Their headstones are no doubt gone and their graves forgotten, but we have resurrected some of their names from obscurity, and we will continue to do the same for other Bullers who are part of our larger family.

Works Cited

Jantzen, Mark. 2010. Mennonite German Soldiers: Nation, Religion, and Family in the Prussian East, 1772–1880. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press.

Klassen, Peter J. 2009. Mennonites in Early Modern Poland and Prussia. Young Center Books in Anabaptist and Pietist Studies. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

As is so often the case, historical context helps us understand our ancestors’ lives and choices. Surprisingly enough, our story begins with Napoleon. As the History Channel so capably summarizes (here), Napoleon was a French military officer during the time of the French Revolution (1789–1799) who rose through the ranks far beyond his peers until he was appointed commander of the entire military in 1796. Three years later he engineered a coup that set him at the top of the French Republic. Eventually, in 1804, the Senate declared him Emperor of the French.

Even when he was fighting on behalf of the revolution, Napoleon sought to conquer territory far beyond what many would consider traditional French territory. Nothing changed in that regard when Napoleon became emperor. If anything, his quest to expand French control only increased.

Of course, the other powers and nations of the day did not wish to serve a French emperor, so both individually and, more often, in alliance they battled Napoleon wherever his armies sought to go. The coalition that interests us most is the fourth, which included Britain, Prussia, Russia, Saxony, and Sweden and spanned the years 1806–1807.

What is of most interest to Mennonites and us Bullers happened during these years. In August 1806 the Prussian king Frederick William III, for reasons not entirely understood, went to war against Napoleon all on his own, with no help from his coalition partners or his military ally Russia. The results were devastating. In the space of nineteen days the Prussian army of 250,000 was literally decimated through the deaths of 10 percent of its soldiers; another 150,000 were taken as prisoners, as well as 4,000 artillery pieces and over 100,000 muskets (see here).

Not only was the Prussian army destroyed completely as an effective fighting force, but Napoleon also added Prussian territory to his realm. The effect of all this on the psyche of the Prussian/German people was devastating, and it prompted the Prussians, after Napoleon’s advance was turned back and his power weakened by the Russians in 1812, to rebuild their offensive might as fully as possible and to add to that a second layer of military capability available for protecting Prussian home territory.

|

| Soldier of the Prussian Landwehr |

As might be expected, the edict was enforced with different degrees of rigor in different regions and likewise encountered different Mennonite responses from place to place. Some government officials overlooked Mennonites who did not comply, while others sought to register every last male. Some Mennonites refused to be registered at all (even though registration did not automatically lead to military service), while others adhered to the law. Of interest to us is Adalbert Goertz’s record of registrations for the Schwetz district, which reveals that all males regardless of their age were registered, including Jacob Buller, 56; Heinrich Buller, 26; Jacob Buller, 9 (all from Przechowka); and Jacob Buller, 45 (Ostrowo Kämpe; see here, table 8).

Although it seems that only a few Mennonites actually saw action, and that generally voluntarily, the proverbial writing was on the wall. The long-standing exclusion of Mennonites from military service was slowly but surely eroding.

It is probably no coincidence that Mennonites—and Bullers—in the Neumark and the Schwetz areas began to immigrate east to Volhynia and Russia during the following several decades. Indeed, all but a handful of members of the Przechowka church moved to the Molotschna colony in 1819–1820 and 1823–1824. As we noted previously (here and here), all the Buller families likewise disappeared from the Neumark area between 1806 and 1826. The most reasonable explanation is found in the growing movement toward universal conscription (i.e., all males subject to the draft) within Prussia during this time. (There is no better account of this development than that found in Jantzen 2010.)

The Mennonites who left in the 1810s and 1820s were shown to have acted wisely in the early 1830s, which is when we take up the story with regard to Neumark (this is not to say that other Mennonite areas were unaffected; they were, but our concern is Neumark). On 16 May 1830, the Mennonite Edict of 1789, which previously had been operative only for the province of Prussia (not the entire Prussian kingdom), was extended to West Prussia (i.e., including Neumark and the Schwetz area) as well. Stated simply, this edict gave Mennonites a choice: serve in the military, like all other Prussians, or pay an extra tax and suffer the loss of some civil rights, including the right to buy land that was nonexempt (i.e., that carried the responsibility of military service).

The extension of the edict’s terms over the Neumark area met with stiff opposition, as “all forty-three heads of household [in Brenkenhoffswalde] went on record as rejecting the option of serving in the military” (Jantzen 2010, 115). When officials attempted to collect the additional taxes and to limit the sale of property according to the terms of the edict, the Mennonites appealed to Frederick William III to uphold the terms of their charter. Frederick “said that he would like to help the Mennonites, but he could not exempt them from the obligations borne by other citizens” (Klassen 2009, 87)

Over the course of the next few years, therefore, the Neumark Mennonite communities arranged to leave their home of seventy years behind. Elder Wilhelm Lange (here) negotiated permission with the Russian government for forty Mennonite families to emigrate to the Molotschna colony, and so it was that

in the summer of 1834 twenty-eight Mennonite families and ten Lutheran families who had joined them left for Russia. There they established the community and congregation of Gnadenfeld. Just as this group had transmitted important impulses from the Awakening movement to the Vistula Mennonites, now too their congregation became a transmission belt for infusing Mennonites in Russia with new attitudes toward missions, education, and spiritual renewal. (Jantzen 2010, 117)

As noted earlier (here), these “new attitudes” played a key role in the development of the Mennonite Brethren movement during the middle of the nineteenth century.

Although the spirit and values and descendants of the Neumark Mennonites lived on in Molotschna and far beyond, the community ceased to exist in 1834. There are no doubt Bullers buried in and around the villages of Neu Dessau, Franztal, and Brenkenhoffswalde. Their headstones are no doubt gone and their graves forgotten, but we have resurrected some of their names from obscurity, and we will continue to do the same for other Bullers who are part of our larger family.

Works Cited

Jantzen, Mark. 2010. Mennonite German Soldiers: Nation, Religion, and Family in the Prussian East, 1772–1880. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press.

Sunday, June 12, 2016

Mennonites in Neumark 2

The initial post about the Neumark (aka Brandenburg, Driesen, or Netzebruch) Mennonites surveyed the beginnings of the settlement and sought to answer questions related to the emigration: When did the emigration occur? From where did the Mennonite families come? Why did they wish to move? A followup post addressed two additional questions: Why did the Prussian officials want the Mennonites to settle in the Netzebruch? Who owned the land on which they settled?

During the seventy years that Mennonites lived in the area, the inhabitants of Brenkenhoffswalde and Franztal exercised a greater role within the religious and political life of the Prussian Mennonite community, even within Prussian politics, than one would expect of two relatively small villages.

As previously mentioned, the early settlers of Brenkenhoffswalde “met in the homes of the members until the available rooms were too small. The government then gave them a building site for a church free of charge, and the funds for the building were donated by the Dutch Mennonites” (Hege 1957). So it was that on 8 November 1778 the Brenkenhoffswalde church met in its own building; Franztal followed suit nine years later, in 1787.

H. G. Mannhardt offers additional background about these Mennonites by identifying the group from which they derived (i.e., the Przechowka church):

To be clear, the Przechowka church was not the only Mennonite church in the Schwetz/Culm area; there was another (Frisian) church in Schönsee, as well as other Mennonite churches at villages somewhat more distant.* Mannhardt’s point is that the Przechowka church was of the Groninger Old Flemish group, as were the Brenkenhoffswalde and Franztal churches.

Thanks to the Dutch Naamlijst der tegenwoordig in dienst zijnde predikanten der Mennoniten in de Vereenigde Nederlanden (here), we know the names of some of the preachers of the congregation at Brenkenhoffswalde: “Andreas Voet (Foth), Ernst Voet (Foth), Peter Jansz, Jacob Schmidt, and Peter Isaack” (Mannhardt 1953). The Peter Jansz/Jantz listed is probably the Brenkenhoffswalde preacher who, in 1814, “spent twenty-four hours in jail for resisting registration” for military service (Jantzen 2010, 93).

The most famous Mennonite figure to be associated with Brenkenhoffswalde, however, was not even born into a Mennonite family. Once again, Mannhardt explains:

In late eighteenth-century Prussia, one could not easily change from one faith or church to another, for example, from Lutheran to Catholic or Lutheran to Mennonite. Joining a Mennonite church was especially limited, to prevent military-age males from converting in order to avoid military service. Lange, having served as the state-appointed teacher in Brenkenhoffswalde, was permitted to join the Mennonite church, though not with the benefit of thereby avoiding military conscription. Mennonite churches in the Vistula Delta rejected such converts, but Brenkenhoffswalde clearly permitted them (see Jantzen 2010, 116).

Lange soon rose to prominence within the local congregation, then among the West Prussian Mennonite churches at large. As elder (from 1810 until his death in 1841), Lange exercised considerable authority and influence both in his own church and in Mennonite churches across West Prussia (as evidenced, e.g., in his letter to Elder Peter Wedel of Przechowka; for additional letters, see the Bethel College Mennonite Library and Archives here).

It seems likely that Lange also influenced the practices of the Brenkenhoffswalde church in a significant way when the congregation encountered a new challenge in the early nineteenth century. At that time “many groups hostile to the government were formed, and in consequence all meetings of private groups were prohibited, including the Mennonites. The only exception made to this ruling concerned meetings held under the auspices of the Bohemian Brethren” (Hege 1957). The church “at once formed connections with the Brethren [aka Moravians] and continued to meet unmolested” (Hege 1957).