Five hundred farmers can’t be wrong. And it’s their opinion that irri[g]ation is crop insurance for central Nebraska.

Alvah Hecht, agricultural agent in York county, estimated that was the number of farmers attending the 4th annual York county irrigation tour. Altho the irrigation systems on each farm visited differed, the principle of “getting the water when and where it’s ne[e]ded” is the same.

Alvah Hecht, agricultural agent in York county, estimated that was the number of farmers attending the 4th annual York county irrigation tour. Altho the irrigation systems on each farm visited differed, the principle of “getting the water when and where it’s ne[e]ded” is the same.

FOR INSTANCE, there was the sprinkler system C. P. Buller has used on his farm near Henderson since 1946.… [the rest of the article appears below]

Yes, that’s him—Grandpa Buller was one of the earliest irrigators in York County. After two emails and a phone call, the rest of the story is now ready to be told.

If you recall from the earlier post (here), the 160-acre Lushton farm included 80 acres on the south that Grandpa and Grandma owned and 80 acres north of the shelterbelt that they rented from Grandpa’s older brother Peter.

Dad tells me that in 1946 Grandpa had a well drilled on the west end but south of the shelterbelt (i.e., on Grandpa’s land). They used that well to irrigate several fields.

For example, they ran a ditch to the south and irrigated corn using siphon tubes, a method that was still used into the latter decades of the twentieth century (and still may be used, for all I know).

They also pumped water out onto the ground and let it run east along the shelterbelt, where it collected in a hole, then was picked up with a booster pump and pumped to the sprinkler mentioned in the article.

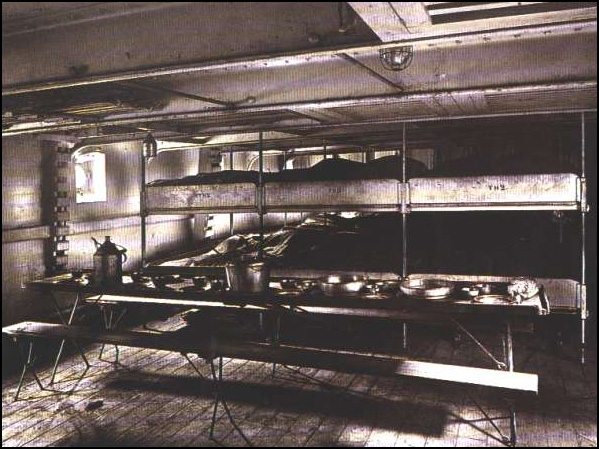

Remarkably, Suely and Dad scanned and sent to me several pictures of that arrangement.

The photo above shows the John Deere GP running the booster pump with a belt. Grandpa is standing behind the tractor; the man smoking the pipe next to him is Alvah Hecht, the York County agent who is quoted in the newspaper article.

In the background you can see sprinklers irrigating the pasture; you can also see the roof of the barn peeking up behind the car.

This photograph shows the sprinkler system a bit better. Grandpa is in the background walking back toward the tractor; Alvah Hecht and the other county official are leaned up against the car. Far in the distance are a few cattle grazing in the pasture. Both of these photos are taken from a spot west of the farmstead looking toward the southeast or straight east.

It is reasonable to imagine that these photos were taken around the time of, and maybe in preparation for, the 1949 irrigation tour. That explains the presence of the county agents with Grandpa but no one else—there is certainly no sight or sign of 500 York County farmers.

I never knew before that Grandpa was, in fact, an irrigation pioneer in York County. Using the well he had drilled in 1946, he ditch-irrigated corn and, with the help of a John Deere and a booster pump, sprinkler-irrigated both the pasture and the milo field on the hillside. Like all of you, I knew he was special, but this adds another facet to my image of him.

P.S. These were not the only photographs that Suely and Dad scanned and sent. Keep watching for a photo of one-year-old Malinda Franz…

**********

The Lincoln Journal article continues:

Roger Weber Leroy uses garden hose with connections on steel pipe to get the needed water to his corn. Besides a well, Raymond Ronne, Henderson has several dams constructed from which he pumps water to his fields.

Bryce Tracy, by using an electric motor, pumps water to his pasture, garden, shelter belt, and corn fields. He floods his brome and alfalfa pasture by bordering the area. John Wocher, does something that others say “can't be done.” He is irrigating on the contour. He pumps water from a large basin up to the higher ground, then is able to farm the land in the basin.

OPERATING A 1,200 acre farm north and west of York, Wayne W. Harrington irrigates 250 acres of corn land. He uses two wells, one pumped with a caterpillar diesel and one with propane. The one pumped by diesel puts out 2,000 gallons per minute.

Herman Fenster, Bradshaw, irrigates has land by an underground tile and soil soaking canvas system. This is a system used in Texas and California that Fenster had seen in operation. He explained this was expensive to install but he feels that it will pay for itself over a number of years because he can water ten acres more of land with the water saved by being carried in canvas ducts rather than in ditches.

THE HARRINGTON farm was the last stop of the tour. Here the York chamber of commerce and Harrington fed the farmers a ton and a half of watermelon plus several hundred bottles of pop. At the Harrington farm the recently constructed 15,000 bushel corn and 6,000 bushel small grain crib and the new air conditioned hog barn attracted nearly as much attention as did the irrigation system. According to Hecht, this was the,most successful of the tours held in the county.

Bryce Tracy, by using an electric motor, pumps water to his pasture, garden, shelter belt, and corn fields. He floods his brome and alfalfa pasture by bordering the area. John Wocher, does something that others say “can't be done.” He is irrigating on the contour. He pumps water from a large basin up to the higher ground, then is able to farm the land in the basin.

OPERATING A 1,200 acre farm north and west of York, Wayne W. Harrington irrigates 250 acres of corn land. He uses two wells, one pumped with a caterpillar diesel and one with propane. The one pumped by diesel puts out 2,000 gallons per minute.

Herman Fenster, Bradshaw, irrigates has land by an underground tile and soil soaking canvas system. This is a system used in Texas and California that Fenster had seen in operation. He explained this was expensive to install but he feels that it will pay for itself over a number of years because he can water ten acres more of land with the water saved by being carried in canvas ducts rather than in ditches.

THE HARRINGTON farm was the last stop of the tour. Here the York chamber of commerce and Harrington fed the farmers a ton and a half of watermelon plus several hundred bottles of pop. At the Harrington farm the recently constructed 15,000 bushel corn and 6,000 bushel small grain crib and the new air conditioned hog barn attracted nearly as much attention as did the irrigation system. According to Hecht, this was the,most successful of the tours held in the county.